Tlingit Botanical Expressions

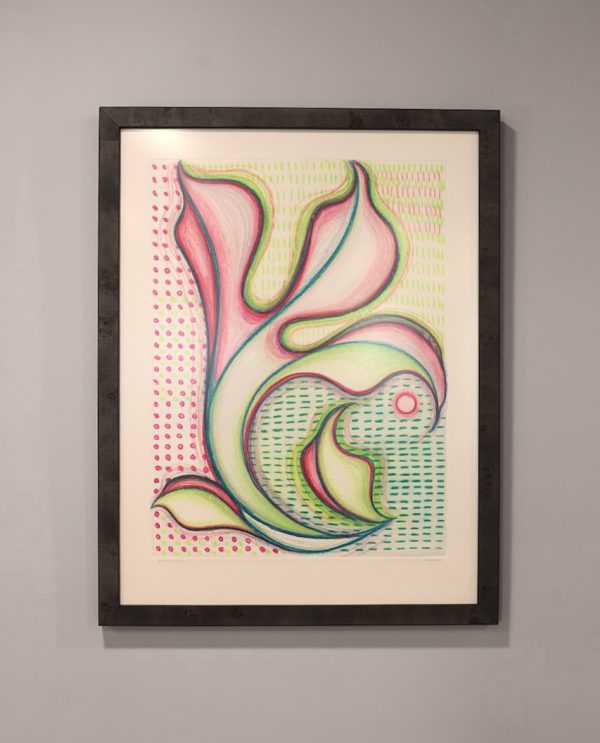

Monoprint pair: intaglio ink, aquarelle pastel on paper; 21×28″.

Much to my surprise, my experiments in botanical study though paint, ink, and weaving became political.

Over the course of many hundreds of years, Western aesthetic preferences have dictated and shaped dominant understandings of what qualifies as “Indigenous art.” Even within Indigenous communities, there is a deep reverence for “tradition” as it relates to lineage and ancestry—sometimes to the point that master Indigenous craftspeople now gatekeep creative practices that were once likely engaged by the majority of community members prior to Western contact.

However, when we look to historically female-gendered art forms—both contemporary and customary—we often find vast differentiation in design, technique, and precision. This is especially evident within Tlingit beadwork, where formline principles are formally difficult to employ due to the fluid, irregular nature of laying down beads. Here, we see a wide visual spectrum of creativity. Formally, beadwork and appliqué appear to possess a rare autonomy, expressing stories and imagery with little scrutiny. After years of research and reflection, I attribute this lateral creative freedom within Indigenous communities to the relative lack of monitoring from the Western art world. Because historically female-gendered art forms were deemed significantly less valuable than their male-gendered counterparts, they were left to develop and transform organically.

Beaders and sewists—regalia makers—were free to influence one another and to absorb outside cultural influences, shaped by the availability of tools and materials: wool blankets, mother-of-pearl buttons, glass beads, and later, sewing machines, earring findings, and baseball caps. At the foundation of these practices exists thousands of years of epistemological knowledge carried through stories, songs, cultural practices, and artworks rooted in ethics of interconnection and balance. As such, these expressive, freeform, and rapidly evolving designs actively participate in the living continuum of our cultures.

The plant forms I move through in this work are inspired by the beaded seaweed designs that animate our ceremonial dance regalia—specifically the seaweed that borders my dancing blanket, which once belonged to my mother and was beaded by my mother, auntie, and grandmother. At the same time, the influence of Western leather tooling—absorbed through growing up around cowboys in the Southwest—is undeniable. Translating my relationship with this oceanic organism through water-based monoprinting allows me to communicate an ever-expanding and far-reaching experience of Tlingit culture.

In this contemporary moment, I have access to patterns, colors, materials, and equipment that speak to Indigenous resilience and cultural continuity, despite persistent forces of erasure. These expressions may not immediately read as textbook “Native,” yet they tell a story of Indigenous people healing—becoming emotionally and environmentally safe enough to imagine a life as professional artists. A life that includes being nominated for a residency in the Hamptons, walking unfamiliar streets without agenda, admiring meticulously tended gardens, spending two uninterrupted weeks in a studio with two print presses and a generous printmaker, free from the pressure of income-driven production—and asking what seaweed might look like when all of these conditions are allowed to be true.

Thank you to my time with Sam Havens at The Church Sag Harbor in 2025, and to Zach Feuer who nominated me. Gunalchéesh to my Auntie Dee for encouraging me to frame my prints, and to Jerrick Hope-Lang who let me curate a show at Aan Hít where they are currently available for acquisition.